History of the IBEW

The nucleus of our Brotherhood formed in 1890. An exposition was held in St. Louis that year featuring “a glorious display of electrical wonders.” Wiremen and linemen from all over the United States flocked to Missouri’s queen city to wire the buildings and erect the exhibits which were the “spectaculars” of their era.

The men got together at the end of each long workday and talked about the toil and conditions for workers in the electrical industry. The story was the same everywhere. The work was hard; the hours long; the pay small. It was common for a lineman to risk his life on the high lines 12 hours a day in any kind of weather, seven days a week, for the meager sum of 15 to 20 cents an hour. Two dollars and 50 cents a day was considered an excellent wage for wiremen, and many men were forced to accept work for $8 a week.

There was no apprenticeship training, and safety standards were nonexistent. In some areas the mortality rate for linemen was one out of every two hired, and nationally the mortality rate for electrical workers was twice that of the national average for all other industries. No wonder electrical workers of the Gay ’90s sought some recourse for their troubles.

A union was the logical answer; so this small group, meeting in St. Louis, sought help from the American Federation of Labor (AFL). An organizer named Charles Cassel was assigned to help them and chartered the group as the Electrical Wiremen and Linemen’s Union, No. 5221, of the AFL.

A St. Louis lineman, Henry Miller, was elected president of that union. I.O. Archives photos show him to be a tall, handsome man with broad, powerful shoulders; keen blue eyes; and reddish-brown hair. To him and the other workers at that St. Louis exposition, it was apparent their small union was only a starting point. Isolated locals could accomplish little as bargaining agencies. Only a national organization of electrical workers with jurisdiction covering the entire industry could win better treatment from the corporate empires engaged in telephone, telegraph, electric power, electrical contracting and electrical- equipment manufacturing.

Henry Miller was a man of remarkable courage and energy. The first Secretary of our Brotherhood, J. T. Kelly, said of him, “No man could have done more for our union in its first years than he did.” Miller packed his tools and traveled to many cities of the United States to work at the trade. Everywhere he went, he organized the electrical workers he met and worked with into local unions.

Although the going was rough in those early days, Miller seemed impervious to personal discomforts and endowed with boundless energy. He “rode the rails” with his tools and an extra shirt in an old carpetbag. Many times the receiving committee on his arrival in a city was a “railroad bull”—a policeman who chased him and tried to put him in jail for his unauthorized mode of travel.

Nevertheless, a great deal was accomplished in that first year. Locals chartered by the AFL and other electrical unions were organized in Chicago, Milwaukee, Evansville, Louisville, Indianapolis, New Orleans, Toledo, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Duluth, Philadelphia, New York and other cities.

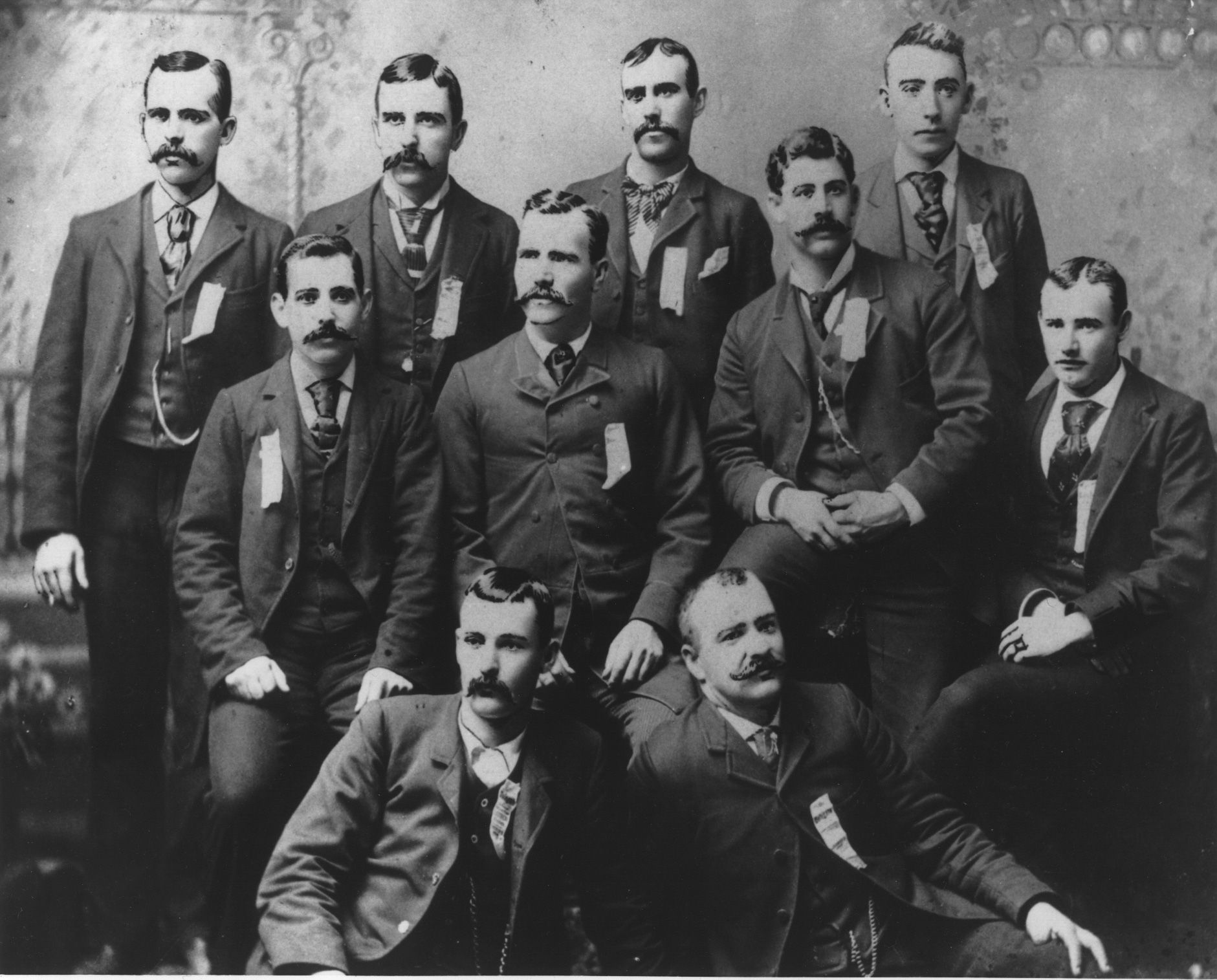

A first convention was called in St. Louis on November 21, 1891. Ten delegates attended, representing 286 members. The 10 men to whom our Brotherhood owes its life and the cities they represented are:

Henry Miller, St. Louis, Missouri

J. T. Kelly, St. Louis, Missouri

W. Hedden, St. Louis, Missouri

C. J. Sutter, Duluth, Minnesota

M. Dorsey, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

T. J. Finnell, Chicago, Illinois

E. Hartung, Indianapolis, Indiana

F. Heizleman, Toledo, Ohio

Joseph Berlowitz, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

H. Fisher, Evansville, Indiana

The founders of our union met in a small room above Stolley’s Dance Hall in a poor section of St. Louis. It was a humble beginning. The handwritten report of that First Convention in our Archives records Henry Miller’s thoughts:

“At such a diminutive showing, there naturally existed a feeling of almost despair. Those who attended the Convention will well remember the time we had hiding from the reporters and trying to make it appear that we had a great delegation.”

The name adopted for the organization was National Brotherhood of Electrical Workers. The delegates to that First Convention worked night and day for seven days drafting our first Constitution, general laws, ritual and emblem—the well-known fist grasping lightning bolts. The Convention elected Henry Miller as first Grand President and J. T. Kelly as Grand Secretary-Treasurer.

bejatc, History, IBEW, International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, Union

You must be logged in to post a comment.